Thinking Like a Scientist

Turns out science is a mindset, not just a methodology. And it's surprisingly hopeful.

This month, I set out to write a blog about space and the scientific process, planning to learn more about hypotheses and tests and objectivity. Instead, reading the words of notable scientists and inventors, I found something unexpected: hope.

I read stories of scientists working for decades to contribute to a body of research or solve a problem unlikely to be solved in their lifetime. People willing to step into uncertainty and bet their reputation on an idea that others believed impossible. A commitment to what Albert Einstein called, “years of searching in the dark for a truth that one feels, but cannot express.”

Training as a scientist forces humans towards uncertainty, objectivity and many, many failed hypotheses. These states are not comfortable for most of us. Even if we will never be a scientist, how can strengthening those muscles improve our thinking and decision making? Here are a few behaviors to consider.

Question All Your Assumptions

To get to a true breakthrough, scientists must employ what philosophers call “first principles.” Imagine you're facing a tough decision or tackling a big project. Instead of relying on assumptions or traditional methods, you take everything apart, down to the core facts. From there, you rebuild your understanding from scratch, using only what you know to be true.

In coaching, we call this identifying your “limiting beliefs.” In your organization, this may look like rules or processes or ways of doing that are actually holding back progress versus supporting it.

The problem is, it’s really hard to objectively question ourselves or think beyond constraints. Some questions to consider:

What assumptions are you making about your work or your life that are not actually facts? Start by making a list of all your assumptions and what you believe to be the facts and then systematically assess them.

What rules or processes are you following that may actually be holding you back?

Think like your competitor or worst enemy. If you were trying to put yourself out of business or beat yourself in a competition, what steps would you take?

Stop Trying to Control the Outcome

Back in my P&G days, I worked on new product launches. As the marketing leader on my brand, I partnered with a product development leader (scientist) to test these new product concepts.

I clearly remember wanting certain concepts to win - I could already imagine the exciting marketing campaign that concept might inspire. I wanted to control the outcome. That wasn’t my partner’s goal; she thought of each concept as a hypothesis that she was testing with no attachment to the outcome. She simply wanted to get to the best outcome. Thank goodness for the R&D team.

She and I spoke recently and she reflected on the freedom she felt as she started her PhD program and embraced scientific inquiry. She built hypotheses, assuming a fair chance of success and a fair chance of failure. When her hypothesis was wrong, she learned something - a failed hypothesis isn’t a personal failure.

Scientists seem to have a different relationship with failure than the average human. Most of us do what we need to do to win. Scientists do what they need to do to learn. What if we could shift our focus from winning to learning?

Try taking one important effort in your life and shift your language for a week. Speak about it in terms of hypotheses and experiments and what you’re learning. Resist the urge to be certain. If something goes wrong, report on what will change moving forward versus characterizing it as a failure.

Set Aside Time to Think

Multiple players in the AI space launched “agents” this week that can interact in human-like ways. AI is growing more powerful and knowledge has never been cheaper, so it may seem counterintuitive to recommend that you spend more time thinking. But I believe thinking has never been more important.

Start by getting up from your computer and going outside for a walk. Don’t schedule a call or listen to a podcast during your walk, just throw your mind open. Let yourself be bored. Daydream. Allow your brain to make connections.

A surprising number of scientific breakthroughs have happened while on walks: Darwin, Tesla and Heisenberg all wrote about landing on the essential insight for their work while on a walk. While I don’t plan to make any scientific breakthroughs on my walks, I almost always make a new connection or have a new thought.

----

In her magnificent book, Braiding Sweetgrass, the botanist and poet Robin Wall Kimmerer discusses her life’s work integrating scientific inquiry and indigenous wisdom.

Describing her first conversation with her college advisor, Kimmerer remembers telling him that she chose botany because she wanted to know why asters and goldenrod look so beautiful together. Her advisor told her that that was not science and enrolled her in General Botany so she could “learn what science is.”

It took her many years to return to the question of beauty and, in posing her original hypothesis, to discover that these two plants grow together because they are not only beautiful to humans, but also beautiful to bees, making them one of the most attractive pollination targets in a meadow.

She reflects that “had my advisor been a better scholar, he would have celebrated my questions, not dismissed them. He offered me only the cliché that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and since science separates the observer from the observed, by definition beauty could not be a valid scientific question. I should have been told that my questions were bigger than science could touch.”

The Earthrise photo inspired bigger questions about the environment in the late 1960s. May we all ask the big questions, seek truth backed up by data and be “better scholars” and scientists over the coming months.

A place to indulge my love of poetry, books of all kinds, and finding the perfect song for the situation, old-school mixtape style.

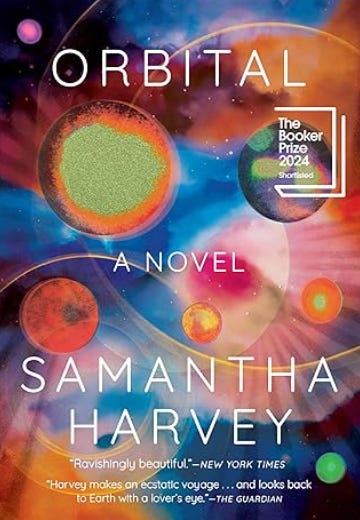

This beautiful, beautiful novel first inspired me to write a blog about space. It follows six astronauts on the International Space Station circling the earth and making observations about human existence and the planet: “Continents and countries come one after the other and the earth feels – not small, but almost endlessly connected, an epic poem of flowing verses.”

“We shall not cease from exploration And the end of all our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. Through the unknown, remembered gate When the last of earth left to discover Is that which was the beginning; At the source of the longest river The voice of the hidden waterfall And the children in the apple-tree Not known, because not looked for But heard, half-heard, in the stillness Between two waves of the sea. —T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding.” Four Quartets, 1943.

Arguably the catchiest song about space ever written. And perhaps an appropriate end to my struggles writing this blog: “And all this science, I don’t understand / It’s just my job five days a week.” Turn this up and enjoy the weekend!

I am an experienced coach and facilitator for executive teams and leaders. To learn more about my services, visit my website.

To get my monthly newsletter directly in your inbox, please subscribe.

Brilliant as always, Meredith -- this is great advice (though admittedly challenging to follow)! My favorite book along these lines is "Think Again" by Adam Grant. There was also some recent research showing that entrepreneurs who "that embraced the practice of rigorously formulating and testing hypotheses consistently outperformed their peers." See here for a summary of both items I just mentioned: https://www.inc.com/jessica-stillman/new-research-confirms-adam-grant-right-be-smarter-more-successful-think-like-scientist.html